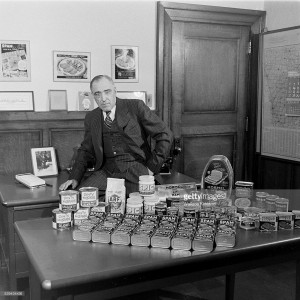

Jay Catherwood Hormel

September 11, 1892 – August 30, 1954

George Hormel’s only son was born in Austin in 1892 and was named for George’s Uncle Jay Decker and close friend S. D. Catherwood. Jay showed a flair for entrepreneurship and innovative thinking even as a child, working up money-making schemes around town. When the academic environment at Princeton did not appeal to him, Jay returned to Austin and showed up at his father’s office, dressed in a suit, ready to learn the family business.

“You can’t learn a business from the top down,” his father told him. “You’ve got to learn by working with the men on the production line. There you’ll see for yourself how to during out a quality product… Can you learn all that by sitting behind a desk and pushing papers?” Jay went home, changed into overalls, and went to work in the receiving yards of the plant, unloading hogs. For the next two years, he worked in each department of the plant, learning by doing, taking on roles of greater responsibility. In 1916, after having served an educational apprenticeship, he was made a vice president of the company.

With America’s entry into the First World War, George Hormel hoped that his son might be deferred from military service, but Jay was eager to enlist. When he received his draft notice in 1917, he was the first draftee from Minnesota to report for training at Camp Dodge and was inducted on September 5. He eventually received a commission as a second lieutenant and was posted to France in January 1918. While serving in France he met the woman who would become his wife, Germaine Dubois – they married in 1922.

After the war Jay assumed greater leadership of Hormel & Company, especially after his father’s retirement in 1927. From the very start of his work overseeing the company, Jay showed a talent for far-reaching planning. In 1928 he dissolved the old Minnesota corporation of the company and reincorporated it under the more favorable business laws of Delaware, a move which enabled him to sell of 60,000 shares of common stock that brought in $3.3 million in fresh capital for much-needed construction of new facilities. Jay officially took on the role of president of the company in 1929, the same year that the Great Depression broke.

A testament to the company’s solid foundation, which George had bequeathed it, and in no small part due to Jay’s extremely capable leadership, Hormel & Company not only survived the hard years of the Great Depression, it also made a profit and continued to pay quarterly dividends to its stock holders at a time when 13,000 million people were unemployed and 9,000 banks had failed. Jay’s innovation was in large part responsible for that.

Just as sausage had saved the newborn company during the financial crisis of 1893, so did Hormel’s new Flavor-seal ham help the company weather the drought of the Great Depression. The demand for a quality product from a reputable company was so strong that even during the worst years of the depression, production of Flavor-sealed ham rose from 226 million pounds to 325 million pounds.

If the company’s continued survival and good financial health were important to its stockholders, it was even more important to the men and women employed at Hormel. Hormel & Company was by this time Austin’s single largest employer, and the fact that Austin workers continued to bring home steady paychecks meant that the town was spared much of the hardships that were bedeviling other communities.

Jay’s knack for product innovation also extended to new ideas for the company’s labor force. One of his ideas – an annual wage program called “straight time” which guaranteed an average of 40 hours work throughout the year, regardless of seasonal fluctuations, and an Old Age Retirement Plan that reduced paychecks by $.20 a week (there were no federal retirement programs at that time) – was misunderstood and misrepresented by union organizers, and the Hormel workers went on strike in November 1933. For three days tensions in Austin ran high, as labor disputes in that era were usually violent confrontations, but cooler heads prevailed. Jay negotiated a settlement and the strike was resolved after three days. In a moment of wry irony, the same union leadership that had objected to Jay’s ideas in 1933 the very next year asked for a guaranteed annual wage, and by the end of 1934 the entire plant was on “straight time” pay, just as Jay had wanted to implement in the first place.

In order to stay ahead of competition from other meat packers such as Swift and Armour, Jay developed a new canned meat product which consisted of spiced ham and shoulder meat. The new product entered the American cultural lexicon as Spam in 1936.

Jay’s focus on worker satisfaction led to the implementation of year-end bonuses in 1937, and the following year a Joint Earnings Plan which gave workers a personal investment in company performance as well as a share in the profits. Jay also developed an employee credit union at a time when such institutions were nearly unheard of, and he required that supervisors must show a minimum of three written warnings before any employee could be fired.

Jay’s philosophy of business and employee relations was best explained by a speech he gave to the Owatonna Rotary Club. “It is my belief that labor troubles would not occur if business could understand labor and the fundamental rights which labor demands,” he said. “The idea that an employer is the lord and master of his own business is an antiquated notion. If you are an employer, you have a job and a trusteeship… Give labor the fair treatment which is it’s right and labor’s right to organize will never harm you.” The results of this ideology were clear to see – even in the Great Depression, Hormel & Company employed 4,495 people and the company continued to grow.

With the onset of the Second World War, Hormel & Company ramped up operations as an essential war-materials processor. The company contributed more than just food products or money to the war effort, however – more than 1,961 Hormel employees served in the armed forces during the war. Jay promised every company employee who served in the military that they would receive a two-week vacation with pay and the guarantee of a job after the war. “In any case,” Jay wrote in an open letter to all of Hormel’s workers then in uniform, “your old job will be here for you. The person who has taken your place will have to find the next best job.” In all, 951 former employees returned to work at the company, and Hormel hired an additional 121 ex-servicemen. But ‘ was painfully aware that 67 Hormel men were lost in the war, and never came back to their southern Minnesota town.

After his father’s death in 1946, Jay became Hormel’s chairman of the board and guided the company through the turbulent post-war years as the United States struggled to find its footing. In spite of uneven production demands and target adjustments, Jay was able to introduce a sick leave program and group insurance plans at a time when few other American companies offered such benefits.

Jay C. Hormel died on August 30, 1954, after a series of heart attacks; he was 61 years old. An innovator and idea-man from the very beginning, he was also forward-thinking in his attitudes toward community and corporate citizenship. “Business does not exist apart from humanity,” he said in 1940. “Business is not a vehicle for just getting. Business is a vehicle for giving – a vehicle for getting by giving.”

Do you know someone that has made an impact on the City of Austin? Submit a Pillars of the City nomination for next year!